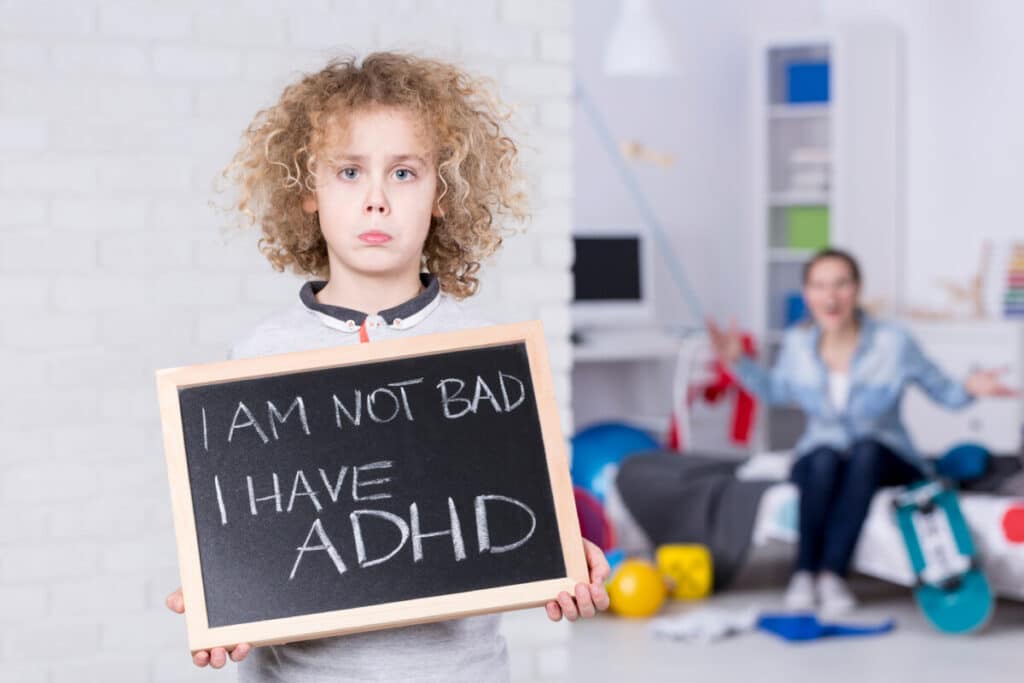

I Have ADHD. Here’s What Helped Me in Elementary School.

So here’s the thing: kids with ADHD are everywhere, and we don’t mean to be troublemakers. The fact of the matter is, that one in five children experience mental health disorders in a given year, yet half of those children do not receive the help they need. Unless kids with ADHD develop healthy cognitive habits and a positive self-image in elementary school, studies have shown that the problems only get worse; so, what can be done?

To help an ADHD child, develop a flexible routine, describe desired behavior to them, help them organize information, give them chances to move around, guide them through tasks and activities, and give positive feedback. Be patient and focus on long-term results, and success will follow.

Kids with ADHD are generally misunderstood; we get yelled at, we get sent to the principal’s office, we get phone calls home, and we start to believe that we really are troublemakers, doomed to remain on the fringes of society. To grow into a successful, confident adult, I needed a lot of help from patient, caring mentors. Here’s what they did, and why it worked.

Flexible Routine

Routine, routine, routine. We absolutely need routine, and we love routine, but often cannot stick to one of our own accords. One of the hallmarks of ADHD is a lack of executive function in the brain; in other words, our brains have a hard time assigning appropriate levels of importance to the tasks at hand. If we’re overwhelmed, it can be especially difficult to find the motivation for anything.

As you can imagine, this makes it incredibly difficult to develop, remember, and stick to a schedule throughout the day–let alone day after day after day. But that’s exactly what school is: the same routine for 35 to 40 weeks for years on end.

The best way to enforce routine for an ADHD kid is to be flexible when there are difficult days or moments of distraction. We never know how we’re going to feel. Some days, we need to stand up and do some jumping jacks or walk around the room. On other days, we may want to talk about something that’s on our mind or work on something with our hands.

A flexible schedule that can accommodate these moments is ideal because after the needs of the moment have been met, there is something concrete to come back to. Without routine, it is easy for ADHD kids to get bored or engage in impulsive behavior because they don’t know where else to direct their inner restlessness.

I had a teacher who always designated the same part of the day for math homework. I knew that I needed to do my math worksheets, but I also loved to read. Sometimes I kept two or three books on my desk at a time, rotating through them based on whichever one was the most interesting at the moment. During math time, I would put a book in my lap and sit with my head down, thinking that the teacher wouldn’t notice me reading under my desk. Surprise! She noticed.

Instead of getting mad at me and trying to enforce the scheduled activity at hand, she told me that as long as my work got done and I didn’t distract the other students, I could read quietly.

This kind of flexibility was exactly what I needed because reading books gave my brain the stimulation I needed to then channel focus into my math assignments. Flexibility will look different for each student, but understanding his or her individual interests and capabilities will help you know when to give them a moment, or when to direct them back to the routine.

Behavior Descriptions

“Pay attention!” “Aren’t you listening?” Kids with ADHD hear these things all the time. Our minds often wander, and when that happens, body language sure gives us away. It’s not that ADHD kids mean to be rude, it’s just that they haven’t yet learned that their actions are perceived that way.

To help a student with ADHD learn how to regulate their behavior, explain to them how that behavior looks and how it makes other people feel. For example, my mother once told me, “When you raise your hand and blurt out the answer before the teacher finishes saying the question, that hurts other kids’ feelings because they don’t get a chance to share what they know. Can you try answering only two or three questions each day, so that the other kids get a chance?”

Regular reminders from my mom helped me regulate the know-it-all impulse to blurt out what I knew. Even if I had to sit on my hands, I was practicing letting others speak. Eventually, the positive behavior stuck.

One teacher developed an acronym for helping ADHD students remember how to display attentive body language: SLANT. Sit up straight, Lean your body toward the speaker, Ask and answer questions, Nod your head ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ and Track the speaker with your eyes.

It may seem like these behaviors are obvious, but young children are just beginning to learn how to display prosocial behaviors and how to interpret body language. By describing desirable behavior to them, you can help them learn how to follow directions and come to understand what “Pay attention” and “Listen” really mean.

Organize Information

When I was little, I used to bombard my mom with questions about the activities of the day: “We’re going to the park,” she would say. “And then?” I would ask. “And then we’ll have lunch.” “And then?” I persisted. “And then we’ll play with the dog.” “And then?” “And then we’ll do chores and have dinner.” “And then?” “And then it will be time for bed.” And so on. Bless her.

Believe it or not, one of the best ways you can help a kid with ADHD stay engaged throughout the day is to practice a “now and next” sort of dialogue. People with ADHD like to have a plan (even if we struggle to stick to that plan), and knowing what activity is coming next can help immensely with focusing on the task at hand. Teachers helped me stay focused when they explained what we were doing next and why the current activity was helping us get there.

Now, as an adult, I repeat this method to provide myself with sources of motivation. For example, if I know I need to clean the kitchen one day, I will make plans to have friends over in the evening. Knowing that people are coming over provides me with the motivation to get up off the couch and do the dishes. It may sound strange, but it’s incredibly effective!

Another form of organizing information is breaking it down. Describe each composite part of the thing you are trying to teach, and the child will have an easier time processing those pieces of information because they no longer feel bombarded with a mass of information they cannot even begin to understand.

This takes time, especially in a classroom setting, but you may be surprised at how many kids actually benefit from slower, organized, and simplified instruction.

Moving Around

Ah, the restlessness. Sometimes we just have to get moving! You may notice that some students have an unusually hard time staying in their seats or not being fidgety. This behavior can be frustrating because it distracts other students and detracts from the lesson. Fortunately, there are easy, subtle ways to give ADHD kids a chance to use their energy in the classroom.

My first-grade teacher gave us five-minute movement breaks between subjects. “Put away your books,” he would say, “Now stand up.” Everyone would stand up. “Hop in place ten times!” A room full of giggly kids hop asynchronously. “Raise your hands above your head!” And so on. Even in higher elementary grades, these were welcome breaks for everyone, not just kids with ADHD. Sitting at a desk for 6 to 8 hours a day is hard for a child!

Another teacher had classroom chores for us to do, and she deliberately assigned the most active jobs to kids like me. She would tell me, “Alright, take this stack of papers and give one to everyone,” which gave me the chance to walk about the classroom and use some of my energy. My fifth-grade teacher even designated the back row for kids who needed a chance to stand up during the lesson without causing a distraction.

Fidget toys are another great way to allow for subtle, non-distracting movement. My sister, who also struggles with focusing during school, loves to fidget with things that have unique textures. In a stroke of pure genius, my mom made “fidget necklaces” for her.

Each necklace had an interesting object like a pom-pom, plastic pouch of dough, or spinning rings. These necklaces gave my sister the chance to keep her hands busy so that her mind could stay engaged with the lesson.

I could go on and on giving examples, but the point is: yes, energetic kids can be a handful, but there are dozens of ways to let them use that energy without being disruptive.

Adult Guidance

Every Christmas, I would ask my parents for the newest object that had captivated my interest: a telescope, a midi keyboard, a drawing pad, a science kit, a harmonica, and so on.

When I received each item, I was thrilled to learn about and engage with what I was sure would be a lifelong skill. I was going to be an astronomer, then I was going to be an author, then I was going to be a musician, then–! But every single time I began engaging in a new skill or hobby, I quickly lost interest, and the item began collecting dust in my closet.

Granted, this behavior is, to some extent, fairly normal for a kid. But a characteristic of ADHD is hyper-fixation, or our tendency to become totally engrossed in something we find interesting or exciting. This means we can adopt a new hobby, spend dozens of hours doing nothing else but that very thing, and then discard the interest before the week is out.

Parent Engagement

One thing I wish my parents had done–though they were incredibly generous and accommodating–was engage in the activity with me. If someone said, “How’s the music composition going? What have you written with your midi keyboard so far?” that was just the motivation I needed in order to push through the resistance of developing a new skill.

Adults who ask questions and follow up with ADHD kids help immensely to buoy their interests and facilitate further engagement.

Hyperfixation

In fourth grade, we had to complete a booklet of information about the wildlife in our home state. The project was to include a section on plants, a section on animals, and a section on the environment.

When I began researching, I became totally obsessed with the birds of prey that were native to my state. I couldn’t decide between a hawk, a condor, or an eagle, so I asked my teacher if I could write a report on all three.

The reports were supposed to be three pages, and she told me that as long as I met the requirements for the booklet sections overall, I could write as much as I wanted. So, newly hyper-fixated on birds of prey, I wrote nine extra pages, proudly stapled them into my extra thick booklet, and promptly forgot about all of it two days later.

Not every student is going to be conveniently hyper-fixated on scholastic subjects. More often, the hyper-fixation will involve cognitively stimulating activities like video games. I wasn’t officially diagnosed with ADHD until I was in college, and the doctor looked at me and said, “I’ll bet you like video games.”

Startled by this uncanny and seemingly unrelated observation, I replied, “Yeah…?” He went on to explain to me that, like Adderall, video games stimulate the brain and “scratched the itch” of hyper-fixation. All of a sudden, it made sense why I was better able to do my homework after a level or two of Pokemon.

Normally, we motivate kids by telling them, “After your homework, you can play games,” or “After your chores, you can have friends over.” This often works, but for ADHD kids, it can have the opposite effect and create apathy or impulsive anger.

Sometimes, it can be more effective for an adult to engage in the interest alongside the kid, allow them to do the extra birds-of-prey report, allow them to play a level or two of their favorite game, and soon enough, their brain will have received the boost it needs to keep going and focus on less desirable tasks. It may seem backward, but trust me, it works.

Positive Affirmation

Last but not least, words. Words mean everything to us. Kids with ADHD spend most of their time in school being told that they are bad kids, that they can’t focus, and that they’re weird. After getting in trouble with adults and being avoided by peers for days and weeks and even years on end, it isn’t hard to see why we start to believe it.

One of the realities of ADHD is emotional dysregulation; as with other restless or cognitive impulses, we cannot regulate feelings of anger or insecurity, so we hyper-fixate upon them until we spiral out of control. Emotional dysregulation is like having a bad sunburn: even a simple slap on the back can be incredibly painful.

Instead of yelling at your kid or getting frustrated with their struggles and differences, focus on their strengths and the things they do right. Comment on those things. (“I noticed that you held your sister’s hand on the way to the bus stop. Thank you for being such a great big brother.” or “That’s a beautiful drawing! You’re a talented artist. I’ll bet you’ll be good at artistically describing things–should we try that in the essay that you need to write?”)

Because we often hear so many negative things about ourselves, these positive comments are precious and rare, and we remember them.

Some of us have found ways to cope with our cognitive struggles, others of us have yet to navigate that mental and social labyrinth without getting bored or discouraged (we’ll do it later, we promise). I can’t help but wonder what difference it would have made for so many of my friends to have had the help of patient, caring adults when they were in elementary school.

Because self-esteem affects the trajectory of so many aspects of life, it is crucial to help your son, daughter, or student understand that they are loved, that they are a good person, and that they can and will be successful in life.

By using the aforementioned tools, help from medical and psychological professionals, and focusing on your relationship with the child, you can make a tremendous difference in the habits they develop and the person they ultimately become.